Introduction: Why this book does not justify chattel slavery and why it instead upholds the law and provides manumission for Onesimus

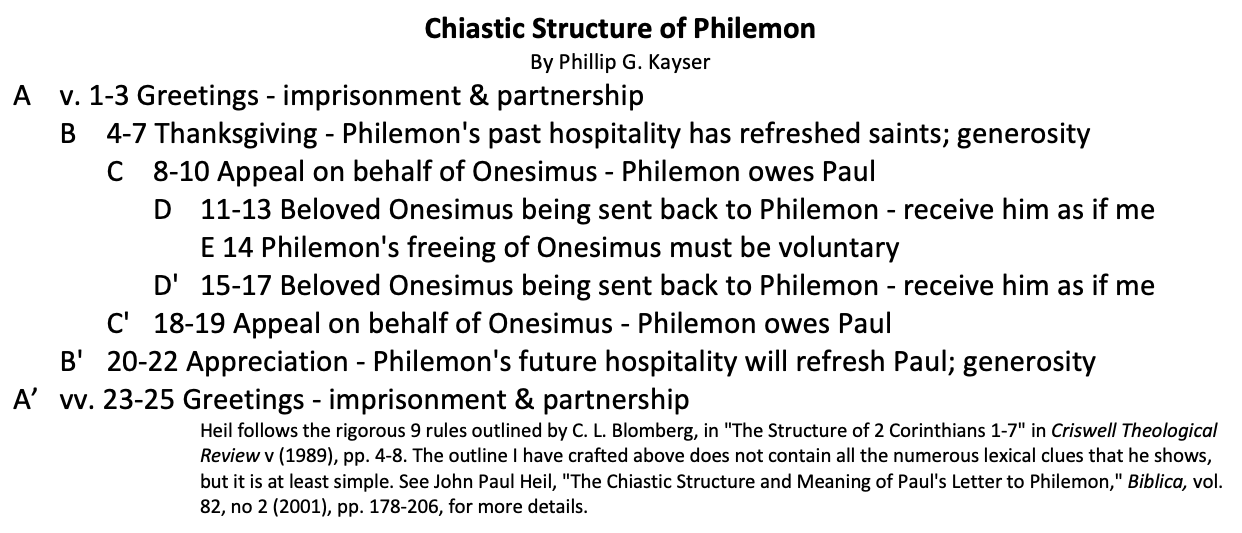

Philemon is a remarkable book on several levels. For example, it is yet another book that has a perfect chiastic structure. John Paul Heil has given a massive amount of proof, but just looking at the results in your outline should be sufficient to show the parallelism. And knowing the structure hugely helps in the interpretation. And believe me, there is a lot of controversy on this book. False interpretations go from the extreme of saying that this book justifies the ownership of kidnapped or any other kind of chattel slaves to the other extreme that it is a radical abolitionist document that overthrows the Old Testament and outlaws slavery. When it is structured right, you will see that it upholds the law but rightly interprets that law as moving people toward liberty. Slavery is not the ideal. This is a book about a slave being freed and what a good deed such emancipation was.

But in addition to its remarkable structure, Philemon is also a remarkable example of sensitive communication. Paul is very gingerly tip-toeing through legal, relational, and financial issues as he seeks to intercede on behalf of Onesimus, a runaway slave. If you know the laws of that time, you know that runaway slaves were not treated well by Romans. Nor were those who harbored them. So Paul sends Tychicus to be an escort and a protection to Onesimus as he travels back to his former master to make things right. And though Philemon had the legal right to continue to own Onesimus, Paul very carefully asks him to free Onesimus - giving several reasons why he should appreciate the opportunity of doing so. So it is a masterful example of very careful and sensitive communication. I think it is a model for all of us when we deal with sensitive issues. Don't be a bull in a china shop. Be like Paul.

It is also a remarkable testimony to God's grace in both master and slave, and how God's grace makes all of us equals before His throne. Martin Luther once said that all of us are runaway slaves like Onesimus, and we all need a Kinsman Redeemer. Onesimus is a wonderful example of you and me being freed by the Gospel.

Now, I did mention earlier that some have claimed that Paul was simply returning Onesimus to his chattel slavery status and they have used this book to justify the chattel slavery that occurred in the Antebellum South. After all (they say), Paul was returning a runaway slave to his master. Paul didn't free him or treat him as a non-slave. Verse 12: says, "I am sending him back." Back to what? He's sending him back to his master. And verse 15 says, "that you might receive him forever." That's permanent slavery. That's the claim.

But there are four factors that such writers miss. And even though I could deal with these points as we go through the text, I think we need to understand these points up front.

The first factor that is ignored is that Paul did not have the authority to free a slave. That's why he is sending him back. Instead, Paul asks Philemon to free Onesimus. He is the only one who can legally do so. Look at verse 16. Paul asks Philemon to treat Onesimus "no longer as a slave." Writers like Doug Wilson emphasize the next phrase and claim that Paul was simply telling Philemon that Onesimus should no longer be treated only as a slave; that he is now more than a slave - that he is a Christian slave and is therefore a brother as well. But they insist that he is still a slave who has repented of having run away and now he is going to model to all slaves how they need to submit to their masters forever. But you can't insert the word "only" into the text I just read. Paul is asking Philemon to treat Onesimus "no longer as a slave." He wants the slave status ended.

Second (and this is in opposition to the other extreme as well), Paul was not in any way overturning the Old Testament law. Some assume that Onesimus was a typical kidnapped Roman slave and therefore, even though the Old Testament outlawed kidnapping, that this book says that once a kidnapped slave has been purchased, you have the right to retain him. But as we go through the book, we will see that Paul upholds the Old Testament law. Both extremes miss this point. The law itself made several provisions for freeing slaves, and Paul brings up two Biblically legal possibilities that were before him. He is upholding the Old Testament law. And by the way, the slave laws of the Old Testament were designed to irresistibly move the slaves to responsibility and liberty. And slaves who did not want liberty were shamed by having their ear pierced. And I have written a detailed blog on the restorative nature of God's slavery laws and all of the other penalties.1 They were nothing whatsoever like the racist laws of the Antebellum South. It's more accurate to say that they reflected indentured servitude to pay off a debt. And we will see hints in the text that Philemon was not following Roman law; he was following Biblical law.

Third, Paul is acting as a Kinsman Redeemer in offering to pay whatever is left on the debt that Onesimus might owe. This is one of the two Biblically legal options that are before him. Of course, he is not a literal blood relative, but he is a brother who meets the spirit of Biblical law. Verse 18 indicates that Onesimus may have stolen something from Philemon before leaving (though there is debate on that), but it also indicates that in addition to that wrong, Onesimus still has debt to pay off. Verse 17 says, "if he... owes anything, put that on my account." He is offering to pay for Onesimus' freedom. Then verse 19: "I, Paul, am writing with my own hand. I will repay..." He is pledging to buy Onesimus' freedom if Philemon is reluctant to do it on his own. And Paul has Tychicus travel with this letter so that Onesimus won't have to face his master alone. Paul addresses the legal possibility of redemption, though he is hoping for a different conclusion. But either way, manumission (which means total freeing) of this slave was Paul's intended purpose. I believe this is crystal clear.

Fourth, there is plenty of evidence that Onesimus was not one of the millons of kidnapped slaves in the empire who amounted to chattel slavery. Instead, he was an indentured slave with a very specific debt that needed to be paid off. Why do I think that? Two reasons:

First of all, Paul would have been in direct disobedience to Deuteronomy 23:15 if Onesimus had indeed been kidnapped and sold as a slave. It says, "You shall not give back to his master the slave who has escaped from his master to you." It would be a serious sin to return a slave to his master if that slave was the result of kidnapping (which was what most Roman slavery was about). Indeed, the death penalty was imposed upon anyone involved in kidnapping. There is no way that Paul would have agreed to a slave being maintained in permanent slavery if he had been kidnapped. A lot of commentaries claim that Paul did not free Onesimus because (with 60 million slaves being in the Roman Empire) he didn't want to risk the start a slave rebellion. I think that is ridiculous. Paul would have done the right thing no matter what the consequences.

Second, a godly man like Philemon would not have kept a kidnapped person as his slave for the same reasons. He was a godly Christian who upheld God's law. John makes that clear. So it is almost certain that whatever kind of slavery that Onesimus was in was a slavery that was authorized by the Old Testament. If that is the case, then this book cannot be used to justify the chattel slavery of blacks in early America. In the Bible you could sell yourself into slavery, become a slave to pay off something stolen, become a slave for a time to pay for another crime, or become a slave because of inability to pay off a loan. That kind of indentured servitude was only for a short period of time.

The third reason is that the text of Philemon itself seems to indicate that Onesimus was a Biblical slave because of debt. Jordan Wilson says,

It’s important to note first of all that Paul reserves the right to hold Philemon accountable to “what is required” by the law...

And I'll stop reading there for a bit. He gets the phrase, "what is required" from verse 8 - "Therefore, though I might be very bold in Christ to command you what is fitting" or literally, "what is required." That word ἀνήκω refers to ethics or what is required in the law.2 Paul had repeatedly stated that he never commanded anything that he could not back up with the Old Testament. What is required is not something new - it is what is required by Biblical law. So back to Jordan Wilson again:

It’s important to note first of all that Paul reserves the right to hold Philemon accountable to “what is required” by the law should he not accept Philemon back “no longer as a slave”. The fact that ostensibly Philemon expects more payment of labor from Onesimus and feels cheated by his departure suggests this was a debt repayment situation. Little is known about the status of Onesimus’s slavery and we cannot assume that Philemon was holding him perpetually, treating him as cattle or that Philemon had acquired him through any unlawful means. In fact, given what we know about transcendent principles of Biblical law regarding slavery combined with Paul’s commendation of Philemon’s record of faithfulness, it would make sense that Onesimus had been initially received as a slave rightfully. There are many such possibilities. It’s quite possible that Onesimus had become destitute and sold himself into Philemon’s care. Onesimus could have fallen into insurmountable debt and was working to pay it off. Possibly he was a criminal or a thief and was paying off restitution to Philemon.3

So we have a situation where Philemon is within his biblical rights to keep Onesimus as a slave. Paul recognizes that fact. And if Paul has to, he will appeal to the law of the Kinsman Redeemer and purchase Onesimus. But Paul also wants Philemon to recognize that the Old Testament law was designed to be restorative - and much of what the law was designed to produce in a slave, God's grace and Paul's instruction had already produced in this man. He was a transformed man. The law treated slaves as children in need of discipleship. Galatians 4:1 says that a Biblical slave is no different than an underage child. He is not chattel; he is an image bearer of God in need of discipleship. When slaves were believers, they were released in the seventh year with enough money or livestock that they could start their own business. And during the six years of indentured servitude, the slave was trained (just like a child would be) in responsibility, discipline, future orientedness, submission, industry, skills, and all of the things that would help to make him a productive citizen. Even unbelievers (as Onesimus was) could become converted believers, and when they did, their clock of slavery would start ticking and they would be released in the seventh year - even if the debt had not been paid. So both law and Gospel were designed with a trajectory to prepare people for liberty. In my sermon on 1 Timothy, I contrasted that beautiful Biblical system with the modern slavery of the prison system and saw that the Bible's indentured servitude was infinitely better. So Philemon is a beautiful treatise that upholds the Old Testament law yet shows how grace leads us to liberty. OK, enough by way of introduction.

Overview of the book through the lens of the chiasm

Let's dive into the chiasm point by point and see where it leads us.

The A sections: Greetings - imprisonment & partnership (vv. 1-3; 23-25)

We'll look at the intro and conclusion first - the two A sections. Both sections give greetings. Both mentioned imprisonment. And both mention partnership.

And in both sections Paul is being very discreet - even in this introduction. In other epistles Paul calls himself an apostle or a bondslave of Jesus. But since he is appealing to a friend and does not want to force the issue, he avoids using his title of authority. So he doesn't call himself an apostle. And since he is dealing with Philemon's loss of a costly slave, he does not want to trivialize the significance of this act of manumission by referring to himself as a slave. Instead, he says, "Paul, a prisoner of Christ Jesus, and Timothy our brother..." Paul was willing to make far greater sacrifices for the kingdom than anything that he is going to ask Philemon to do. Verse 1 continues his greetings:

To Philemon our beloved friend and fellow laborer, 2 to the beloved Apphia, Archippus our fellow soldier, and to the church in your house:

Though the singular "you" is used throughout the book, these phrases indicate that Paul already knew by inspiration that Philemon's wife (Apphia), his son Archippus, and the whole church that met in their home would appreciate and value the lessons of this book. And I'm so thankful that God addressed it to the church as well. Apphia was the manager of the house and no doubt missed the help she would have otherwise have had from Onesimus, so Paul wants her to be part of the discussion. But ultimately, Paul's letter will deal with the head of the household. He is the one that will have to make the decision.

Paul asks for God's grace and peace to rest upon Philemon in both the introduction and the conclusion. And both bring other friends of Philemon into this discussion - Timothy in the intro and Epaphras, Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke in the conclusion. This is not a private matter. Since it will be a legal transaction, there are witnesses to what Paul is offering. These were all men who had sacrificed their wealth and their life to serve the Lord. Epaphras was even a fellow-prisoner as a result of his care for Paul - as you can see in the second A section.

So the intro and conclusion are subtle appeals that pull at Philemon's heart strings and make him desire to selflessly serve the Lord even as these other men have done. But it also reminds him that God's grace and peace can easily recompense him for anything he will lose in this request.

The B sections: Thanksgiving - Philemon's past (vv. 4-7) and future (vv. 20-22) hospitality brought refreshment and showed his generosity.

The B sections are thanksgiving for the ministry that Philemon has done in the past (that's the first B section) and thanksgiving and appreciation for his hospitality and ministry in the future (that's the second B section). Each B section highlights that home's hospitality, refreshment, and generosity. And the point is that he is not asking Philemon to do anything that Philemon has not already shown an eagerness to do. I'll just read the two sections because they are so self-explanatory. But I hope these two sections make you desire to open your home in a similar manner. Beginning at verse 4 in the first B section:

Philem. 4 I thank my God, making mention of you always in my prayers, 5 hearing of your love and faith which you have toward the Lord Jesus and toward all the saints, 6 that the sharing of your faith may become effective by the acknowledgment of every good thing which is in you in Christ Jesus. 7 For we have great joy and consolation in your love, because the hearts of the saints have been refreshed by you, brother.

If you were sitting in prison, would your prayer life be so constantly filled with thanksgiving, faith, joy, and consolation? This is a tribute to Paul's close walk with God. He did not allow his circumstances to get him down.

But these verses also show Philemon that Paul never takes Philemon's generosity for granted. He appreciates it; he counts on it; but he never takes it for granted.

The second B section begins at verse 20:

Philem. 20 Yes, brother, let me have joy from you in the Lord; refresh my heart in the Lord. 21 Having confidence in your obedience, I write to you, knowing that you will do even more than I say. 22 But, meanwhile, also prepare a guest room for me, for I trust that through your prayers I shall be granted to you.

What obedience is Paul referring to in verse 21? I believe it is obedience to the Old Testament law. In 1 Corinthians 4:6 Paul said, "that you may learn in us not to think beyond what is written." It is the Scripture alone that can command obedience, and Paul is appealing to the well-known slave laws of the Old Testament. Let me read you Richard Melik's comments.

He urged Philemon to refresh him “in the Lord,” and immediately Paul asked for Philemon’s obedience. Though Paul issued no specific commands, Philemon’s actions were a matter of obedience. This cannot be, therefore, obedience to the apostle—that neither fits a context where no commands are given nor the phrase “in the Lord.” Paul meant that he would be refreshed as his children walked in accord with the will of God. As he saw Philemon respond to a difficult situation, acting in accord with his Christian commitments under the leadership of the Lord and the Holy Spirit, Paul would be refreshed. In this, Paul sounds like the elder who wrote 3 John, “I have no greater joy than that my children walk in the truth” (3 John 4).4

The point is that this whole epistle is founded upon the law of God and motivated by the grace of God. It is not pitting the New Testament against the Old Testament as if our God has evolved into a kinder, gentler, more politically correct god. That is blasphemy. That is the way liberals interpret it. Instead, Paul is thankful that Philemon's whole life is characterized by obedience to the Scriptures. And it is the Scriptures alone that Paul operates from. There is a unity of purpose between the book of Philemon and the rest of the Bible.

The C sections: Appeal on behalf of Onesimus - Philemon owes Paul (vv. 8-10; 20-22)

And it is in the C, D, and E sections that the doctrine of the restorative purpose of Old Testament slavery is introduced in a powerful way. The first C section begins at verse 8.

Philem. 8 Therefore, though I might be very bold in Christ to command you what is fitting, 9 yet for love’s sake I rather appeal to you—being such a one as Paul, the aged, and now also a prisoner of Jesus Christ— 10 I appeal to you for my son Onesimus, whom I have begotten while in my chains,

What's going on? Well, using the law of God, Paul could insist on freeing Onesimus by paying what was owed. He could command that, and no slave owner was allowed by Biblical law to refuse a cash offer. But to do that would make Philemon look like the bad guy and Paul to be the one with a generous heart. And Paul is friends with Philemon; he doesn't want that. Paul wants Philemon to know everything that has happened to Onesimus and wants Philemon to know what a blessing Onesimus would be to him as a freeman who could serve with him. But Paul leaves it up to Philemon whether he would be the generous person or whether Paul would be the generous person. That's all Paul is asking. There is a choice between two options, but both options involve Onesimus' freedom. It's all perfectly in accord with God's law.

And I should point out that Paul is making clear that he is not wearing his apostle's hat here. He is not invoking his own authority. Instead, he is writing as a friend in need - Paul, the aged, and now also a prisoner of Jesus Christ. "I need help. Maybe Onesimus could help me." But though he appeals to Philemon, Philemon knows that he owes Paul. And if Philemon chooses to free Onesimus, Paul will treat it as if Philemon has done it for Paul, because Onesimus is like a son to Paul (verse 10). Also look at verses 20-22.

Philem. 20 Yes, brother, let me have joy from you in the Lord; [I'm going to see this as a gift from you to me. "Yes, brother, let me have joy from you in the Lord;"] refresh my heart in the Lord. 21 Having confidence in your obedience, I write to you, knowing that you will do even more than I say. 22 But, meanwhile, also prepare a guest room for me, for I trust that through your prayers I shall be granted to you.

He's showing confidence in Philemon's generosity because Paul knows from past experience that Philemon is exactly this kind of a generous person. But the way Paul asks this, it is totally up to Philemon, and Philemon comes out shining when he does come through. It's such a delicately worded letter that is looking out for Philemon's reputation, and his honor, and uniting the hearts of Onesimus and Philemon and not just Onesimus and Paul.

The D sections: Beloved Onesimus being sent back to Philemon - receive him as if me (vv. 11-13; 15-17)

But he gets to the nub of the question in the two D sections. In verse 11 Paul makes a play on Onesimus' name - a name that means profitable.

11 who once was unprofitable to you, but now is profitable to you and to me.

Apparently Onesimus was not a good worker. He had been unprofitable - and even more so since he had taken advantage of the trust that Philemon had put in him. But somehow this runaway slave had run across Paul in prison, had gotten converted, and had had such a transformation of his character that he was a new man - a man very profitable to Paul. He was living up to his name. Verses 12-14.

Philem. 12 I am sending him back. You therefore receive him, that is, my own heart, 13 whom I wished to keep with me, that on your behalf he might minister to me in my chains for the gospel. 14 But without your consent I wanted to do nothing, that your good deed might not be by compulsion, as it were, but voluntary.

He could have just sent the money ahead as a cold and calculated financial transaction and the law would have made even a reluctant master forced to sell his slave into freedom - whether he wanted to or not. Of course, Roman law would have allowed Philemon to refuse the offer, but not Biblical law. Anyway, Paul knows Philemon will want to do this on his own, so he makes it Philemon's choice.

I'll return to verse 14 in a bit, but it is clear from what Paul is writing that he is not returning Onesimus to slavery. When Paul commands, "You therefore receive him," it is clear that Paul is not asking Philemon to receive him as a slave. He wouldn't have to command him to do that. What master wouldn’t want his slave back? But to receive Onesimus the way Paul wants him to be received would require a decision on Philemon's part that would be hard; it would cost him some money; maybe a lot of money. To receive him as Paul's own heart means to treat him as he would treat Paul. Earlier he had said to treat him as Paul's own son. He wouldn't enslave Paul's son. Paul wants Philemon to receive Onesimus as if Onesimus was Paul himself. This is strong language.

The second D section is even more clear. It starts at verse 15, where Paul appeals to God's unusual providence in having the two meet.

Philem. 15 For perhaps he departed for a while for this purpose, that you might receive him forever, 16 no longer as a slave but more than a slave—a beloved brother, especially to me but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord. 17 If then you count me as a partner, receive him as you would me.

To receive him forever means for all eternity as a fellow-believer, not to receive him as a permanent slave, as some have thought. That would not have been forever. If this had been just an economic transaction, there would be no joy in it for Philemon, but Paul gives Philemon opportunity upon opportunity to take credit for something that will benefit him, Onesimus, and Paul.

In any case, verses 16-17 clearly contradict the interpretation that says that Onesimus is returning to be a permanent slave. Verse 16 says, "no longer as a slave." He is free if he is no longer treated as a slave. Verse 16 goes on to say, "more than a slave - a beloved brother." Verse 17 makes it even stronger when it says, "If then you count me as a partner, receive him as you would me." Philemon would never receive Paul as a slave. If Paul is a partner, then receiving Onesimus as you would me means receiving Onesimus as a partner. He is going to forgo money so that Onesimus can go into the ministry. And history tells us that he did indeed become a partner in the Gospel, eventually becoming a pastor and then the moderator of the entire presbytery. This is a call for full manumission; full freedom. For defenders of the AnteBellum South to say otherwise is disingenuous.

The heart of the chiasm: Philemon's freeing of Onesimus must be voluntary (v. 14)

But since verse 14 is the heart of the chiasm, it makes clear that Paul is going to let Philemon decide. Even though Paul is willing to pay, he wants Philemon to have the opportunity to get the honor.

But without your consent I wanted to do nothing, that your good deed might not be by compulsion, as it were, but voluntary.

First of all, manumission is a good deed. As long as there are criminals, there will be some kind of slavery - whether it is prison slavery or indentured servitude. But God's law tried to move slaves as quickly as possible to freedom, and freeing a slave was a good deed. The only good deed is a lawful deed, so he is asking for something allowed in the law. Don't pit Philemon against the Old Testament law as so many people have done.

But what does the phrase, "without your consent" refer to? It refers to Paul's desire in verse 13: "whom I wished to keep with me, that on your behalf he might minister to me in my chains for the gospel." Paul knew that it would not be lawful for him to keep Onesimus. Onesimus had to be returned to his rightful master. The law demanded that. But Paul is asking if Philemon would please consider freeing Onesimus so that he could return to Paul and minister to him as his heart longed to do. Onesimus was willing; Paul was willing; the only question was whether Philemon would be willing. Paul did not want his arm twisted into doing this. he wanted this to be voluntary. Manumission of a lawfully procured indentured servant could never be involuntary - unless of course you had a Kinsman Redeemer purchasing him. Otherwise it had to be an act of grace and goodwill - especially since Onesimus had not paid off his debt.

So Paul lays before Philemon two options. Paul was willing to pay Philemon everything that Biblical law would demand as compensation. Or second, since Philemon was wealthy and could afford to do so and loved supporting Paul, he was hoping that Philemon would treat this as a gift to Paul. But either way, the result would be the freedom of Onesimus. All Philemon has to do is to take the legal steps necessary to make sure Onesimus remained a free man under Roman law.

Did Philemon free Onesimus? We are not told in Scripture. But interestingly, archaeologists did find an ancient inscription by a slave in that area that dedicates the monument to the master who freed him, and the master's name is Marcus Sestius Philemon.5 Was it the same person? We don't know. But the slave must have become a somebody to do this. And that ties in with a second piece of evidence. In a letter that alludes to this book of Philemon, Ignatius (the early church father) speaks of Onesimus as being the bishop or moderator of Ephesus. To me it appears that Philemon did indeed bless Onesimus, Paul, and the whole church with this economic gift. Here was a man that moved from slave to being bishop over Ephesus.

Additional applications

Let me end with four more applications.

The first application is that this book speaks of the value of having sanctuary states. And you might wonder where in the world I got that idea. Let me explain. It comes from the date and location that this book was written. Obviously there is controversy on that subject. If he wrote it from prison in Ephesus, it would be written in AD 55. That's very unlikely, and very few people hold to that viewpoint. If it was written from Rome (as the majority seem to believe) it would be written in AD 62. But there are a growing number of scholars who believe there are too many problems with the Rome-theory. It is crystal clear that Ephesians, Colossians, and Philemon were all written from the same place and all three letters were delivered by Tychicus. I won't bore you with all the evidence, but I believe that Ephesians, Colossians, and this epistle were written from Caesarea in Israel in AD 58 while Paul was a prisoner in the Praetorium and ministering to the Praetorian guard. And that's the position I took when I preached on those two epistles.

So that's the background to my application. Why would I say that this speaks to the importance of sanctuary states? Well, neither Ephesus nor Rome were good places for a slave to run to. If I was a runaway slave, I wouldn't run to either place. Some of the treatment of runaway slaves in those cities was barbaric. But just assuming that you didn't get branded or die, both places also had a lot of professionals who worked full-time as self-employed detectives to hunt down runaway slaves for money. They were bounty hunters. That was their full-time profession. These were not people contracted by the owner. These were people who snooped around finding tips on who might be a runaway and after catching him, getting remuneration. And the treatment of runaways was savage. Rome and Ephesus were two of the worst places to run to.

Secondly, to get to Rome he would have had to have traveled by ship, and it would have been impossible for him to hide his identity on that ship. Of course, there are many other reasons why I reject Rome as the place of authorship. But this is one - it is more likely that this runaway would have traveled by land.

So that leaves the Caesarea theory. Caesarea was in Israel and Israel still followed Biblical laws on slavery and eventual freedom. Since Philemon's house was where the church met, Onesimus would no doubt have heard the Scriptures many many times. He may very well have heard the Scriptures that showed the good treatment of slaves in Israel. So in the entire empire, Israel was a kind of sanctuary state. Their law did not allow the return of a slave to any foreigner. And slaves were treated quite well.

So back to my application - I believe there is huge value in setting up sanctuary states today for the unborn and for people who don't want forced vaccinations and for homeschoolers to flee to if they get persecuted. I'm thankful that our Attorney General is making Nebraska inhospitable to sex-slave traffickers. Especially as this country degenerates quickly, it may become increasingly important for Christians to ask states to become sanctuary states. Some states are trying to become sanctuary states for guns and gun manufacturers. Oklahoma for babies. Other states have been asked to consider protecting other liberties.

A second application is that no one should view their current difficult plight as their destiny. Onesimus was an unbelieving slave, was a fugitive whose money was probably running out, yet God's grace brought him to faith, to transformation, and to freedom. Indeed, at least some commentators believe that Ignatius is writing about this Onesimus as the one who later became the moderator or bishop of the neighboring presbytery of Ephesus. The point is, don't be chained by your past failures. Your past failures are not your identity. Christ's call upon your life is what should give you vision. Be driven by the future. Too many people let their past bondage determine who they can be, so they call themselves Gay Christians, or Transgender Christians, or think of themselves as failures. No. Your new identity is not with your old lifestyle. Your identity is in Christ, and if Christ has set you free, you shall be free indeed. In fact, Paul acting as a Kinsman Redeemer may have very well been a subtle clue to Christ as a Kinsman Redeemer completely freeing us from our bondage. Onesimus is a beautiful symbol of what the Gospel can do.

A third application is that we should avoid false dilemmas when we interpret the Scriptures. A false dilemma is "It's got to be either this or that." It fails to realize that there may be other options. Too many interpreters of Philemon present only two options - either this book supports chattel slavery or this book supports abolitionism. Both sides can appeal to some evidence. But neither side does the whole book justice. There is obviously freedom being obtained, but it was obtained in one of the two ways outlined in the law of God. Philemon is not a New Testament ethic that is brand new. It is a Biblical ethic that is consistent from Genesis to Revelation. So the point is, don't let commentaries force you to accept one of two options - especially if both of those options contradict the rest of Scripture. And of the 90+ commentaries on Philemon that I own, most have not broken out of this false dilemma. Just be aware that this reductionism tends to be a problem.

My fourth application is that this book calls us all to humility in our relationships. Paul describes the rich Philemon as a "fellow laborer" and twice calls him his brother. But then Paul calls Onesimus his beloved brother and his own son who ministered to him. Despite his still being a slave, he was also a brother. In Christ we are all equal. There may be offices and authority and roles that God has delegated to us, but in ourselves we are equal and ought to treat each other with the honor and dignity that being in Christ deserves.

There are a lot of other applications we could make from this beautiful book, but we will end with those four. May God bless you. Amen.

Footnotes

-

Schlier (in the Theological Dictionary of the New Testament) says, "In the LXX it is almost always (1 Βας 17:8) found in the legal or political sense (1 Macc. 10:42: διὰ τὸ ἀνήκειν αὐτὰ τοῖς ἱερεῦσι τοῖς λειτουργοῦσι, 11:35; 2 Macc. 14:8. Cf. P. Tebt., 6, 42: τῶν ἀνηκόντων τοῖς Ἱεροῖς. . . In Phlm. 8 in the NT τὸ ἀνῆκον (with ἐπιτάσσειν) denotes not merely that which is fitting but that which is almost legally obligatory, although in a private matter." Schlier, TDNT, s.v. “ἀνήκει,” I:360. The following commentaries are examples of those that take this word as a moral obligation: White, Newport J. D. n.d. “The Epistle to Titus,” in The Expositor’s Greek Testament, vol. 4. New York: Doran. Oesterley, W. E. n.d. “The Epistle to Philemon,” in The Expositor’s Greek Testament, vol. 4. New York: Doran; Huther, Joh. Ed. 1890. Critical and Exegetical Handbook to the Epistles to Timothy and Titus. 4th ed. Translated by David Hunter, with supplementary notes by Timothy Dwight, the notes indicated by the abbreviation My(D). (This commentary is a continuation of the series formerly ed. by H. A. W. Meyer.) New York and London: Funk and Wagnalls. Meyer, Heinrich August Wilhelm. 1880. Critical and Exegetical Handbook to the Epistles to the Philippians and Colossians, and to Philemon. Translated, revised, and edited by William P. Dickson. New York: Funk and Wagnalls. ↩

-

https://www.lambsreign.com/blog/in-which-no-quarter-november-immediately-gives-quarter ↩

-

Richard R. Melick, Philippians, Colossians, Philemon, vol. 32, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1991), 367–368. ↩

-

See footnote 3 in Andrew L. Bennett, “Archaeology from Art: Investigating Colossae and the Miracle of the Archangel Michael at Kona,” The Near East Archaeological Society Bulletin 50 (2005): p. 15. ↩